Pietrangelo Buttafuoco

Pietrangelo Buttafuoco was born in Catania in 1963 and lives in Rome.

He is a journalist and writer.

He has published Le uova del drago (Mondadori, 2005, finalist for the 2006 Campiello Prize, reissued by La Nave di Teseo, 2016), L’ultima del diavolo (Mondadori, 2008), Il Lupo e la Luna (Bompiani, 2011), Il dolore pazzo dell’amore (Bompiani, 2013), I cinque funerali della signora Goring (Mondadori, 2014), La notte tu mi fai impazzire (Skira, 2016), I baci sono definitivi (La Nave di Teseo, 2017), Sotto il suo passo nascono i fiori (with Francesca Bocca-Aldaqre, La nave di Teseo, 2019), Salvini and/or Mussolini (ParerFIRST, 2020).

Among the essays, he published Fogli consanguinei (Edizioni Ar, 2003), Cabaret Voltaire (Bompiani, 2008), Buttanissima Sicilia (Bompiani, 2014), Il Feroce Saracino (Bompiani, 2015), Strabuttanissima Sicilia (La Nave di Teseo, 2017); together with Carmelo Abbate Armatevi e Morite (Sperling & Kupfer, 2017).

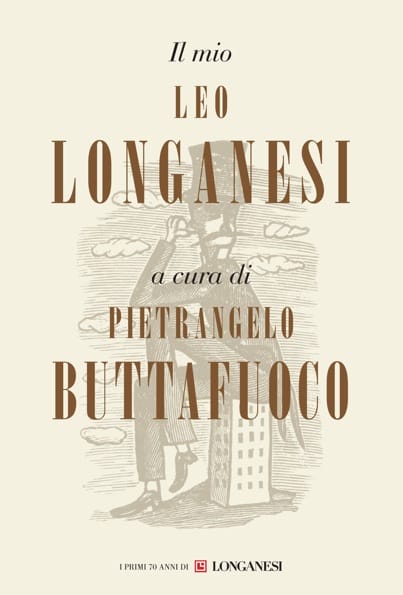

In 2016, for the seventieth anniversary of the Longanesi publishing house, he edited Il mio Leo Longanesi, an anthology of aphorisms, epigrams and short stories.

In 2018, he wrote the preface to La repubblica dei vinti. Stories of Italians in Salò by Sergio Tau (Marsilio, 2018).

He is the author of plays including: Strabuttanissima Sicilia with Salvo Piparo and Il Dolore Pazzo dell’Amore with Mario Incudine.

He writes for Il Quotidiano del Sud.

His latest novel is titled Sono cose che passano and was published in 2021 (La nave di Teseo).

In 2023 he published with Longanesi Beato lui. Panegirico dell’arcitaliano Silvio Berlusconi.

On October 26, 2023, he was appointed president of the Fondazione La Biennale di Venezia.