Paolo Nori

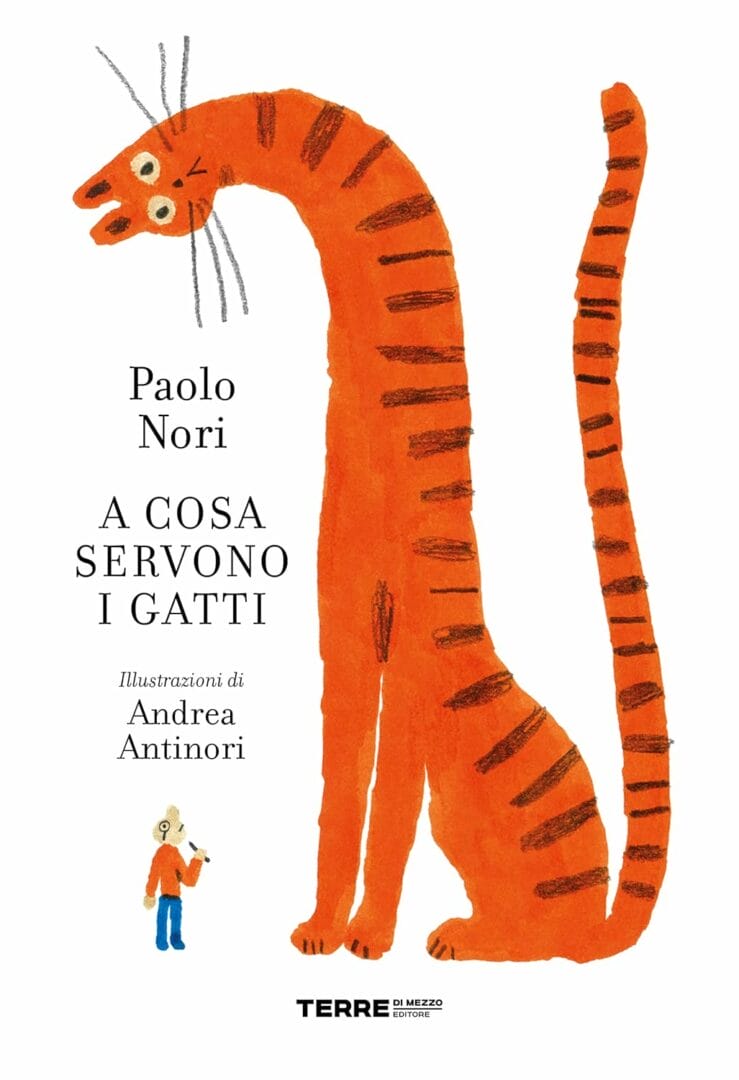

Paolo Nori, who was born in Parma in 1963 and lives in Casalecchio di Reno, holds a degree in Russian literature and has published many books including Bassotuba non c’è (1999), Si chiama Francesca, questo romanzo (2002), Noi la farem vendetta (2006), La meravigliosa utilità del filo a piombo (2012), La piccola Battaglia portatile (2015), I russi sono matti (2019) , Che dispiacere. Un’indagine su Bernardo Barigazzi (2020), Sanguina ancora. L’incredibile vita di F. M. Dostoevskij (2021), e A cosa servono i gatti (2021).

He teaches literary translation from Russian at Iulm in Milan.

He translated and edited works by Pushkin, Gogol’, Lermontov, Turgenev, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Gončarov, Leskov, Čechov, Chlebnikov, Charms, Bulgakov, Arkadij and Boris Strugackij, and Venedikt Erofeev.

He translated and edited for I Classici Feltrinelli Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol', Oblomov by Ivan A. Gončarov, and The Belkin tales by Aleksandr Pushkin.

In 2022 his translation of Fyodor Dostoevsky's Notes from the Underground was released for Garzanti, and in 2023 he wrote the preface to Gianni Celati's Le avventure di Guizzardi for Feltrinelli.

In 2023, Vi avverto che vivo per l'ultima volta. Noi e Anna Achmatova was published for Mondadori.

Also in 2023 he writes and performs Due volte che sono morto, a Chora Media podcast for Rai Play Sound.

His latest book is Una notte al museo russo, published by Laterza in 2024.

Between 2023 and 2024, Mondadori republishes Le cose non sono le cose, Grandi Ustionati e Diavoli in the Oscar imprint. Also, Nori is curator for Discorso su Puškin by F. M. Dostoevsky, due out in 2024. Also in 2024 Laterza publishes Una notte al museo russo.

His last book is Chiudo la porta e urlo, published by Mondadori in 2024.