Enrico Deaglio

Enrico Deaglio was born in Turin, Italy in 1947.

He has lived in San Francisco since 2012. He has worked in print media and television.

He has dealt with the Mafia for 40 years; in 2021 he was a consultant to the Anti-Mafia Commission of the Region of Sicily on the Borsellino murder cover-up, headed by Claudio Fava. Among his investigative books on our recent history, the longest-running is La banalità del bene - Storia di Giorgio Perlasca (Feltrinelli, 1991). He has told mafia stories with Il figlio della professoressa Colomba (Sellerio, 1992), Raccolto rosso (Feltrinelli, 1993), Il vile agguato (Feltrinelli, 2012), Indagine sul Ventennio (Feltrinelli, 2014) and the trilogy of Patria. La bomba. Cinquant'anni di Piazza Fontana (Feltrinelli). In 2020 won the Bagutta prize.

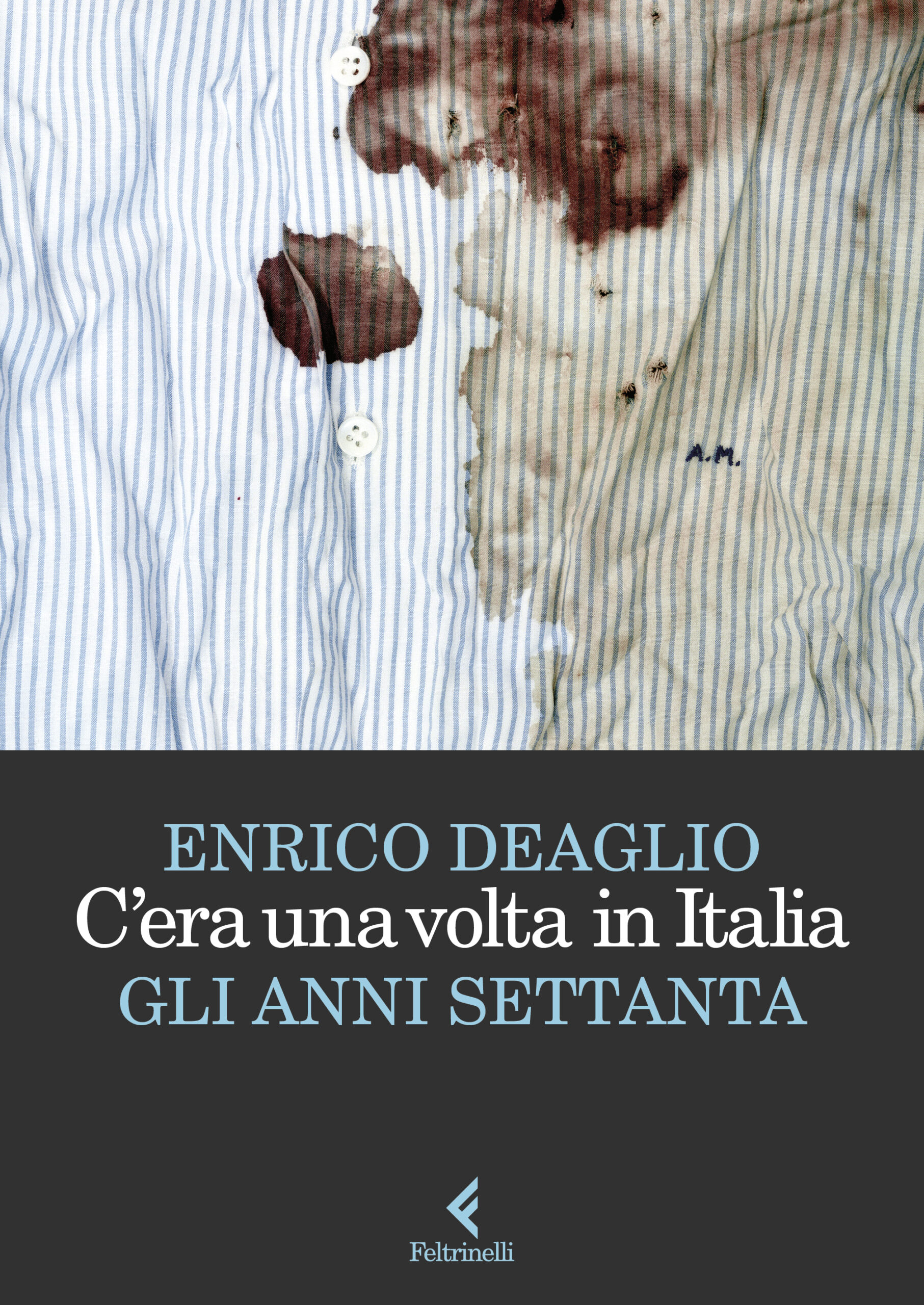

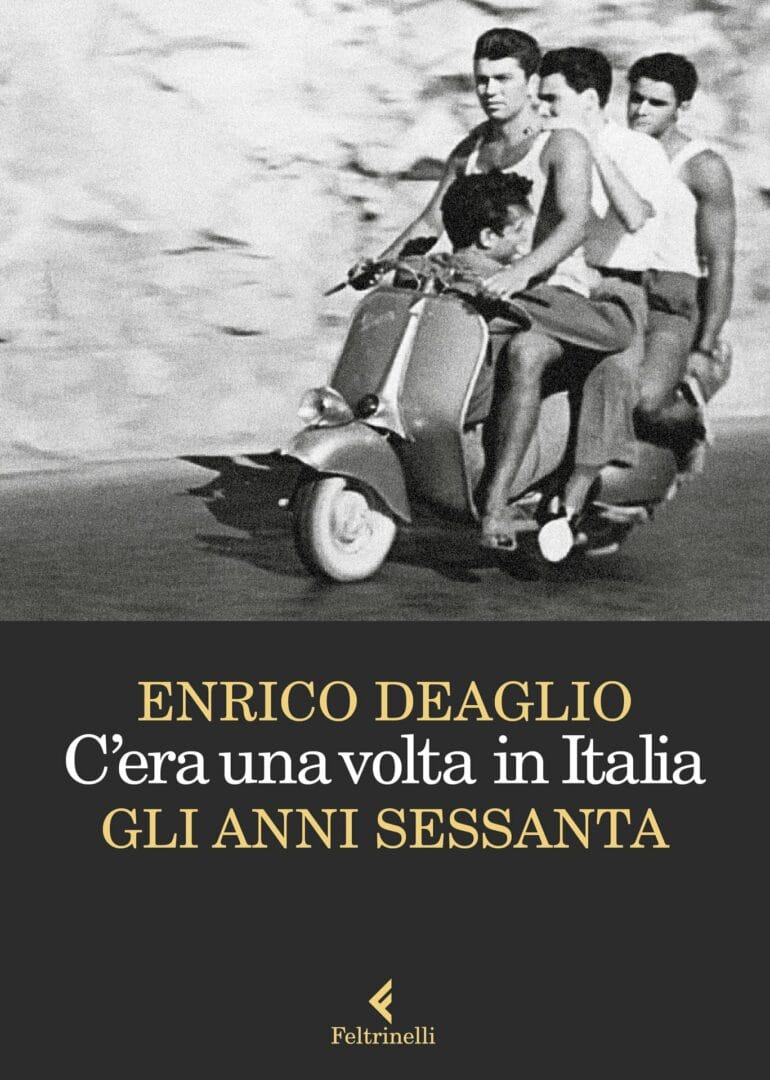

In 2023 he published for Feltrinelli C’era una volta in Italia. Gli anni sessanta, which was followed by C’era una volta in Italia. Gli anni settanta (Feltrinelli, 2024).